I’ve been working on a new tale set in Lucardia that isn’t directly connected to my other plotlines. Something completely stand-alone. Below is a rough draft of the first chapter. I’m curious to know if it’s hitting.

The chapter reads almost like a short story, so I can go that route with a few tweaks if I want to build some momentum. Some authors have gotten works published this way, so I am thinking of trying that route out.

I have several other story ideas I’m mulling over, and I am trying to decide where to devote my energy. I’m only 10,000 words into this one, so if it sucks, I can bail and move on to something else before I get too deep. Let me know what you think!

The Last Knight of Norn

By Scott Austin Tirrell

Chapter 1

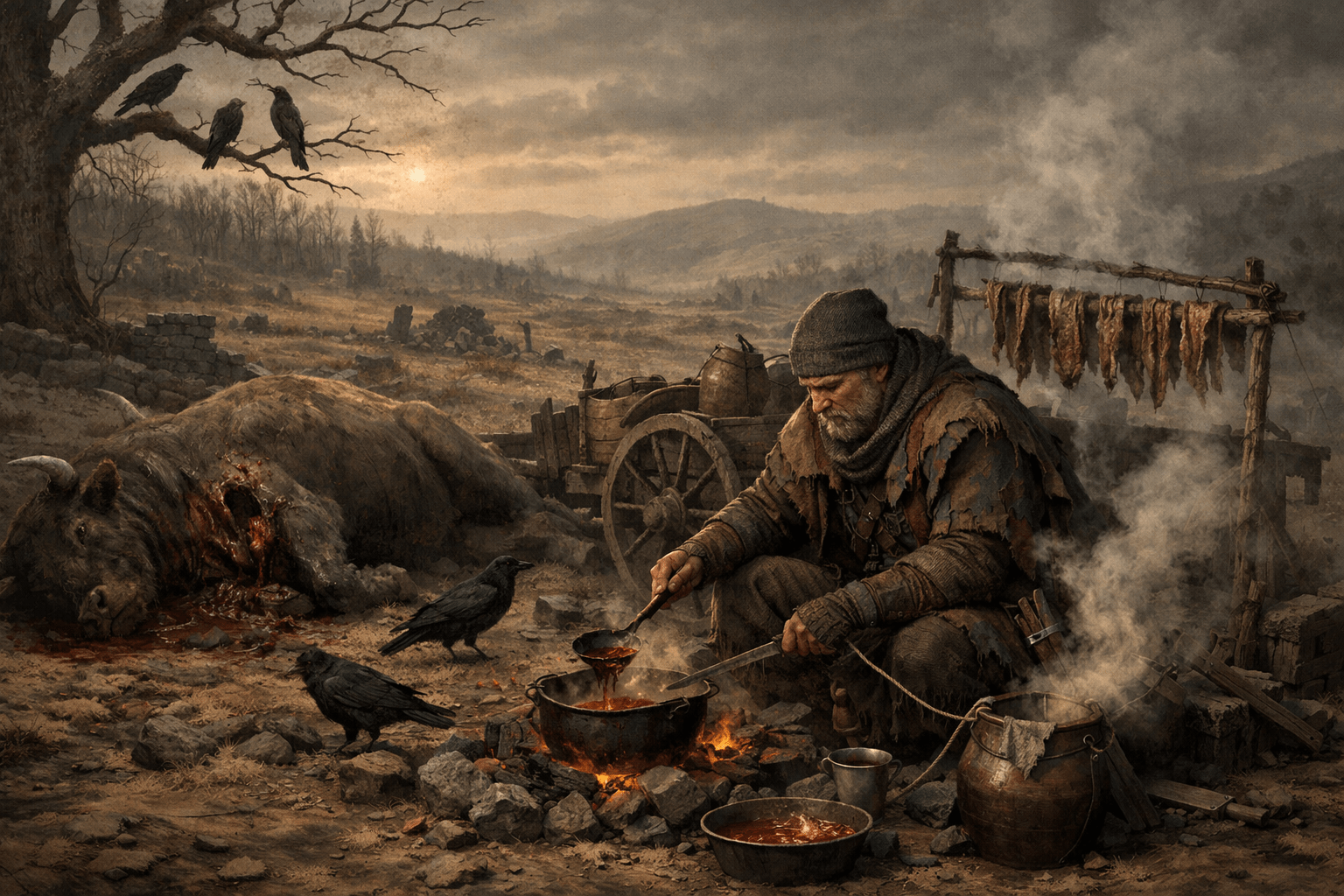

The clamor rising over the hill scattered the crows. They lifted from their meal in a storm of caws, abandoning the deer’s picked bones to the wind. They wheeled once, affronted, and took roost in a dead oak to watch the man and his cart pass beneath them.

The man didn’t look up. “Oh, quit your carrying on. We’re just passing through.” He spit. “The road will soon swallow us again, as it swallows everything—tracks, names, prayers—and then you can return to your meat soon enough… and your gossip.”

Beyond the oak, the land opened into the Scourge—fields the color of old ash, stitched with low stone walls that led nowhere. Here and there, pale shapes lay half-buried in drifted dust: foundations, wagon hoops, a jawbone with teeth still set in it, the crest of a skull turned face-down as if it were ashamed to see what the land had become.

The cart was at least a century old, built of sweet chestnut no longer found in these hills, all having gone the same way as the crows’ roost. It rode low on iron-banded rims gone black and scabbed with rust. The spokes creaked in protest. The axle, dark with grease and mud, groaned wood on wood—an old, sore language that confessed the burden it carried.

There was a line of neat holes on either side of the bedrail where iron had once been bolted, their rust stains still bled down the grain. Krieg, the old-timer who’d traded the cart for a winter’s debt, used to jab a finger at them and swear a cage had been fastened there once. He’d then boast about how he hauled two princes from Westerly Rock to their execution in the times when the Empire still gleamed. No one ever believed him.

The bed was nothing more than planks over a frame—warped ribs with daylight in the gaps, stained by years of hauling manure. Nails stood proud, bent and re-bent, and a cracked rail had been lashed back together with rawhide and a prayer. Rope hung in stiff lengths from the side, and a hook under the rear crossbar clicked softly whenever the cart rocked. In back, empty vessels knocked and clattered—basins, jugs, bottles, fat-bellied barrels bound in iron—every mouth open to the sky, begging for rain. They were more burden than cargo, rattling through each rut as if the cart carried thirst itself.

Up front, the ox—Hob—was just as much a relic—only with breath still in it. He was immense, the color of old earth, and fierce looking—all a show. In his youth, Hob had been the pride of the village, but now his hide was scarred like a map, the hair rubbed thin at the shoulders where the yoke had bitten. One horn had been blunted to a crooked stump; the other was long and ridged, cracked near the tip from years of fighting fence and fate. His eyes were slow and dark, red at the rims from wind and dust, blinking too often—dry, irritated, thirsty. A rope of spit hung from his lip, thick and stringy, and his tongue kept working in a mouth that had nothing left to give.

Hob had hauled heavier loads for longer miles, but he was near twenty now, and thirst had finally begun to win. His nostrils flared with each drag of air, rimmed with dust-caked wetness dried to salt, and his muscles trembled each time his hooves sank. Hob fought against the leather straps and tugged at buckles that no longer matched. But forward was all he knew, so forward he went—one step, then another.

When Hob leaned into the harness, the cart lurched and settled, keeping the driver from dozing. The wheels bit into ruts, iron bands scraping stone, and the load shifted with a muted thump—slow, inevitable, as if the cart had been making this journey for decades and would keep making it long after the ox and its driver became dust.

The man on the front plank was no farmer out for daylight errands. There hadn’t been farmers here in nearly two decades. This man was something the road had kept and hollowed, left intact only because it still had use for him. What use, only the road knew.

This was Orlan.

He sat on the front plank, a fixture nailed into the cart’s bones, shoulders hunched beneath a cloak that had seen one winter too many. It was patched in mismatched squares, dark with old rain and the pipe-smoke that clung to him—a poor answer to thirst, but steadier medicine for his nerves. The coat had never fit right; he’d taken it from a dead man two winters ago. In the right light, the stain of that man’s blood still showed. It was badge and shame together, and he wore it like a debt.

Orlan was missing a glove, lost miles back when he’d pulled it off to rub grit from his eye. It irked him. Gloves were hard to come by, and he doubted he’d find another on this trip. Already his hand was chapped with knuckles split and the skin too small for the bones beneath it, tight as dried hide. He held the pipe with this hand, trying to warm it. It would be a bad day.

Thirst was a constant companion, but it rode him hard this morning. It was a stone behind his tongue and made his mouth taste of rotting meat. When he swallowed, there was always that brief, stupid hope—his body begging for relief—and then the swallow ended, and nothing changed. His throat stayed rough. His head ached as the world narrowed: thoughts shortening, patience thinning, irritations sharpening into rage for no reason at all. Thirst could make a man stupid. It could make him impulsive. He’d been both—but today he couldn’t afford either. He needed to stay sharp. These were not safe roads.

Orlan tapped out the spent marshmallow leaves from his pipe and rubbed his face, a map of small violences: burns from sun and wind, old cuts, a healing bruise around his eye, and the scar along his jaw left by the man who used to own his coat. He wiped dust from the stubble on his cheeks and from the wiry gray hair sneaking out beneath his knit cap. His gaze stayed on the horizon. It narrowed, measuring tree line and bend, the quiet places where a man could vanish, and the world would swallow the sound. He had seen many things, and none of them good. He would never admit it, but fear lived in his eyes, too. He placed his pipe in his pocket and flexed his hand. The missing glove wasn’t a good omen. On roads like these, you watched the smallest shifts in fate—because they had a way of gathering into calamity.

Orlan turned his ear and listened. The Scourge was a silent place once you were past the crows, Hob’s bellows, and the cart’s complaints. Out here, a voice—or even the snap of a branch—meant trouble. But sometimes the trouble wasn’t a sound at all—sometimes it was the moment the wind stopped, and the silence had weight—like a hand closing over a mouth. Orlan checked to be sure his medallion was still around his neck and pulled his sword closer. He didn’t want any trouble, and if he were honest, he didn’t have the strength for it either.

The axle distracted him. It told its secrets in its groans. Hob bellowed back, feeling the drag of grit in the hub. They had traveled a long time together, this pair and him—far, unimaginably far. If the cart and beast meant to leave him for whatever waited beyond, he would know. Not yet. But soon.

Orlan pushed the worry back and spat to the side. With thirst riding him, he hated to waste the saliva, but the fields were poisoned; even the dust, if you took in too much of it, could leave you curled and cramped for days. He’d learned that on his first voyage, and once was enough for a lesson like that.

“This was a mistake,” he whispered. “Maybe we should turn back.”

Hob snorted but kept walking. Even the ox knew Orlan had no other choice.

The cart crested a shallow rise, and the land dipped into a crease of darker earth. Below, threading between stones, ran a thin ribbon of water. Not a river. Not even a proper brook. A stream—maybe only a rivulet—narrow and lazy, the kind you wouldn’t have spared a second glance at in the old world. Here, it was a trap dressed as grace. It caught the light in bright little knives and made Orlan’s throat tighten on reflex. His tongue pressed hard against his teeth, as if he could wring water out of bone.

Hob saw it too. His head lifted. The rope of spit at its lip quivered. He bellowed, and his pace quickened by half a step—just enough for Orlan to feel it through the harness.

“No,” Orlan murmured, not loud, not angry—almost pleading. “Hoo!” He clicked his tongue and brought the cart to a halt before the beast could decide for him. The wheels settled into the ruts. Behind him, the empty kegs knocked, reminding him why he’d come.

Orlan sat still for a breath, watching the stream as if it might vanish if he looked away.

He wasn’t completely without water. He had a fortune in the guise of a canteen—tucked beneath the front plank, wrapped and tied and guarded like a last breath. But he’d already drunk too much on this journey, nearly half. More than he’d meant to. Thirst made you a thief. It made you forget the future’s desperation the moment your tongue turned slick. What remained might last him a day or two, but that wasn’t his worry. As much of a friend as Hob was, he couldn’t spare a drop on the beast. Its purity was for men. But his friend needed to drink, too.

He slid off the cart, and his boots sank into soft ground beside a porcelain doll with a soiled pink dress and a cracked face. The air smelled almost alive. The stream ran over pebbles and leaf rot, and the sound of it—small, constant—felt like a hand at his throat. He crouched carefully, as if the water might bite.

Then he took out the cup from an oilcloth pouch that hung from his belt.

It wasn’t big—no goblet from a lord’s table, no shining treasure for the old world’s ceremonies. It was plain in its shape and worn at the rim, dented on one side as if it had once been stepped on. But it was silver, real silver, made from melted royals minted by kings long dead. The cup caught what little light the day offered with a cold, steady gleam. Each vessel and its magic to decide life or death had grown a certain mystique—as cups often did. It wasn’t quite religious, not yet, but all it took was a prophet to latch onto the idea, and it would be chiseled into church mantels just like the damned Sword and Sun.

He felt the medallion under his jerkin. Blasphemy, it seemed to whisper. Do not let this land tempt you from the path of the righteous.

Orlan dipped the cup into the gentle flow. The water swirled, cool and clear. It always did. That was the cruelty of it—how innocent it looked, how it begged you to believe.

He lifted it into the sunlight and waited. The air felt heavier down in the crease. The hollow held old breath. He had the sudden sense that if he shouted, the land would drink the noise. He had felt that once before. His eyes darted to the horizon. Still clear. His attention returned to the cup.

A long moment passed. Behind him the cart creaked in the breeze. Hob snorted once, impatient.

Then the silver spoke. Not with sound, but with the slow, unmistakable bloom of corruption—an oily shadow spreading along the inside of the vessel, darkening the metal in thin, veined patterns like bruises under pale skin. The water itself did not change. It was only the cup—the last truth-teller left in this land.

Orlan’s stomach tightened.

Poison—one you couldn’t boil away. Poison you couldn’t smell or taste. In a mouthful it might only sour you, make your gut clench and your head swim, the first thin warning of what lived in the water. But it didn’t stay small. It settled into your blood and sat there, patient as rot, until your belly cramped and your joints ached and your mind began to slip like wet rope through a fist. Drink enough—gulp it like an animal at the end of its strength—and it didn’t matter how strong you were or how big. Your guts would turn. Your muscles would seize. Your heart would stutter like a lantern in the wind. And then you were gone. He’d seen it happen more times than he wanted to count. His wife. His children. Friends. So many.

Orlan tipped the cup and poured the water back into the stream as hope poured from his heart.

All of it was death—no use for rinse or ritual. Even too much on the skin was dangerous. He wiped the silver with the edge of his cloak, hard, until the bruise-veins faded and the metal returned to its cold, clean shine.

He was so focused on the cup—on the proof, on the urge to rage at a world that ran water you couldn’t drink—that he didn’t hear Hob move.

Not at first.

What he heard was lapping. Wet and greedy behind him. A mouth working as if it had found salvation.

Orlan’s head snapped around.

Hob had stepped forward, muzzle already in the stream, drinking hard. Not sipping. Not tasting. Gulping like a dying thing.

“No, Hob—” Orlan’s voice cracked, raw with panic.

He lunged, grabbing at the yoke, at the leather straps, hauling with all the strength left in his arms. The ox didn’t flinch. Thirst made water his goddess. He kept suckling, eyes half-lidded, throat working, swallowing poison like mercy, ignoring even the man who kept him fed—because what was hunger beside thirst?

Orlan planted his boots and heaved. The harness cut into his palms. The straps creaked. The ox finally jerked his head up—

Water spilled from Hob’s mouth.

For one heartbeat, Orlan thought he’d saved his friend.

A tremor ran through the beast’s shoulders. His legs stiffened into seizure. His jaw worked uselessly, the tongue pushing out for a moment, and the thick rope of spit snapped and flung into the mud. Hob’s eyes rolled, showing too much white.

“No,” Orlan whispered again.

Hob tried to step back, but his hooves would not obey. He sagged into the harness, the cart jerking forward a handspan, and then he folded—slow at first, as if kneeling, and then all at once, his great body collapsing into the wet earth with a sound like a tree giving up.

The empty kegs in the cart clattered—hollow laughter over a dead thing.

Orlan stood over the fallen ox, breathing hard, hands shaking, the silver cup cold in his fist. He watched the flank rise once—twice—then hitch, then tremble, as if the body were arguing with death. Hob’s eyes stared at nothing. His tongue lay in the mud, already drying.

Sated thirst would kill Hob soon, and there was nothing Orlan could do but bear witness—the death of his mission with it. No, that wasn’t entirely true. There was still one thing he could do, but it would be a last cruelty to his only friend on this road.

Orlan looked both ways. The Scourge spread empty and dead to either side as far as he could see. He was weeks from home on a road he did not know—his mission of life suddenly a failure. He looked to the indifferent heavens, wanting to scream, but he kept it in. He’d carried on like that before when he held the hand of his last dying child. It never changed a thing. There was only one fact before him. The Boken had a line for this: face what you cannot change with resolve.

He drew his knife and rested his hand on the beast’s flank. “Sorry, old boy,” he whispered, and drove the blade into its side. Hob jolted once. Orlan worked fast, slit the belly, and spilled the water before the poison could seep into the blood. Hob shuddered again, but Orlan doubted the ox could suffer more than he already was.

Orlan pulled a large, shallow pan from the cart, set it beneath the ox’s neck, and cut the carotid. The blood came hard at first—hot, black-red, steaming in the cold air—then settled into a thick, pulsing pour that made the mud shine where it splashed. Orlan held the pan steady with both hands, knuckles whitening on the rim. He could feel his throat working as he watched it. The body’s stupid hope again, at the sight of anything wet. The same lie the stream told: drink, and be saved.

He didn’t. Not yet.

Hob’s heart stopped, and so did the blood. Orlan nudged the pan with his boot—about three gallons. He began to search for tinder.

You didn’t gulp blood fresh unless you wanted to hasten death. Every scavenger knew that. Blood could buy you time—wet the throat, quiet the screaming in the skull—but it carried weight too: salt, iron, the dense meat of life. Your body needed water to bear it. Drink too much too fast, and it turns on you. It was a stopgap, a cruel one. But processed, the gap widened. That was what he was after now.

Orlan wished he were back in his village with a woodpile stacked high. He would have distilled every last drop of the ox’s blood. A beast this size carried ten gallons, maybe as much as thirteen, and with his crude still he could have coaxed out several gallons of foul-tasting but drinkable water. Out here, he had neither the equipment nor the fuel. But all hope wasn’t lost.

Orlan watched Hob’s eyes go glassy. A fly landed on the delicate film. They always knew. The last death rattle ran through its flank like a fading drumbeat. Then it was mass and stillness—another friend and fellow traveler turned to meat.

Orlan turned to his reflection in the pan. The blood had already begun to change, skinning over at the edges, thickening as the parched air drank it in. He rubbed his gloveless hand. He hated how his bloody fingers shook. In a day or two, he would run out of water, and after that, he’d follow Hob soon enough. With a little work, this pan, and some twine, he might wring three more days from the beast. It wasn’t much, but it was everything when life was involved.

Orlan forced himself to move.

He circled the cart and began tearing at what little the land offered: dead brush, splintered limbs, the brittle husks of weeds that crumbled in his grip. Everything here was eager to burn, but it would burn fast, so he needed plenty. He found a pocket of dry rot beneath a fallen log, shaved some sticks into curls with his knife, and built a small nest of his gatherings in a shallow depression between stones.

Flint. Steel. One of the few things that still worked the way it always had.

A spark caught, then another. Smoke rose thin and bitter. The flame took—hesitant at first, then hungry. Orlan fed it until it settled into a low burn.

He dragged a small iron pot from the cart’s bed, dented and blackened from a hundred hard meals, and set it near the coals. He laid two stones on either side and made a crude cradle. He poured about a gallon of blood into the pot. The rest he left to clot for later. Nothing was to be wasted now. Not even what sickened you.

He crouched close to the fire and held his hands out to test the heat. The effort sharpened his thirst into a bright, angry point. It made every smell louder: smoke, wet earth, animal heat, iron. His mind went to the canteen—its weight, its promise.

“No,” he whispered. “You must wait until it is unbearable.”

He watched the blood carefully, keeping it from boiling. Boiling drove off what little mercy remained, leaving thicker salt and heavier ruin. It turned a stopgap into salt poisoning. He’d learned that from an old scavenger who died when he failed to follow his own lesson—mouth foaming, belly clenched like a fist. Heat it until it trembles, the man had said. Until it thinks about simmering and decides against it, so you can scrape off the curds and leave only the whey.

Wisdom crumbles in the grip of thirst. That was the second lesson that man taught him.

Orlan kept the flame low and patient, feeding it sparingly. The surface of the blood began to shiver with a slow quiver as something beneath it rose. Dark scum gathered at the edges. Then pale curds appeared—stringy, ugly ropes of denatured life—floating up and collecting into foam.

Orlan leaned in and grimaced.

The smell changed into hot pennies and cooked liver—something the tongue remembered even when the mind wanted to forget. He’d been on the edge of death before, and he’d swallowed this drink then, too. At least this time it came from an ox.

He took a flat strip of wood, used it like a spoon, and skimmed. The curds clung and stretched, reluctant to leave. He lifted them out and let them fall beside the fire, where they hissed and darkened. He worked until the liquid beneath looked thinner, less burdened—still blood, still wrong, but closer to something you could force down without your body rebelling.

Not ready yet.

From the cart, he took a length of cloth—old linen, once a shirt, now a rag with a hundred uses. He found another basin and tied the cloth loosely over its mouth with a cord, making a shallow sieve.

Then he poured.

The warmed blood ran through in a slow, reluctant stream. The rag caught what curds remained, staining dark, swelling with their weight. What dripped into the basin was thinner—more reddish-brown broth than raw blood—still metallic, still alive with salt and iron, but less likely to turn his guts inside out on the first swallow.

He retrieved his silver cup to sample the brew. He drew a draught and stared into it like a soothsayer reading tea leaves. The contrast of silver and red looked obscene, a wicked communion for a wicked world.

He lifted the cup toward his face and paused, listening to the land again. The Scourge lay even quieter than before. No cart. No ox. No crows. The birds had respect for his initiation into the holy order of carrion eater. The entire world held its breath and watched as this man ingested his friend.

Orlan took one sip.

Warmth spread across his tongue. Not pleasant—never—but immediate. The thirst didn’t vanish. It offered no mercy, the way water did. But it softened the razor in his throat, blunted it enough that he could breathe without feeling he was inhaling dust.

He swallowed.

His stomach clenched in reflex, offended by what he’d asked it to accept—blood from another friend. Orlan held still, eyes half-lidded, waiting for it to rise. It didn’t. His body knew better. It didn’t bend to the frail sensibilities of the mind.

He took a second sip, a smaller one. Measured—like everything had to be now. His throat begged for a gulp. He had to stay disciplined, had to remain cruel, to let his body take it slowly so the benefit outlasted the cost. This was the Scourge’s balance.

The relief was shallow and temporary, a borrowed coin you’d have to repay. He felt it in the way his mouth was already drying again, in the way his tongue searched his teeth for wetness like a rat scouring a cracked wall for crumbs. The salt was still too high. He had to go further.

He set the filtered pan on the cart’s bench and tied a length of twine from its lip to the mouth of a stoneware jug on the ground. The broth would creep along the cord, slow as a worm, leaving the heavier grit behind—and some of the salt with it. It wasn’t distilling, but any salt he could remove meant more hours alive. The trouble was time. It would take hours to draw even a gallon through.

His contraption finished, Orlan stood with his hands on his hips and stared at the fallen ox. The broth had steadied him—not calm, never calm, but enough to think straight.

He looked at the stream, bright and laughing, and felt something ugly rise through his ribs. He hated a world that laughed at its own joke. Liquid life flowed there, close enough to touch, mocking him—whispering that he could be a dumb ox too, drink deep, and be sated.

Orlan turned his back to it and poured more blood into the pot. He stirred and skimmed, then did it again. If he could coax even a gallon of drinkable liquid by sundown, he’d call it victory. If the horizon stayed clear and he could make camp, he might tend the fire all night and squeeze out another by dawn.

But beyond that, what should he do? Try to make it back? He was three weeks from home. Even if everything went right, he might wring two weeks of life from the blood. Not enough. He could hope for rain. He looked up at the blank sky, then scanned the horizon for any wisp of mercy. Possible, yes. Likely? No. This part of the Scourge could go months without a drop.

He looked to the road ahead–some highlands bearded with a dead forest. Some of the trees tinted toward green, but it was too far to tell for sure. Perhaps providence would wake from its long slumber and give him what he sought. He wouldn’t be able to fill the kegs, but he could go back with knowledge and bring others. It was his only choice. Either way was a gamble with death—but only one sent him home in defeat.

He would go on foot. Without the cart and Hob’s strength, he had to choose with care. He spread his wool blanket and set down his canteen, the last of his pemmican, knife, flint—then the silver cup. Sword, bow, ten arrows. There wasn’t much left alive in the Scourge to hunt, but a ranged weapon had other uses when resources grew thin, and hands came grabbing.

He surveyed his kit and sighed. Having to travel on foot with all this on his back would require more provisions. His eyes turned to Hob.

Orlan took up his knife and went to the hind quarter, working fast before the flies came—skin first, then flesh—only enough to carry. He hated to leave the rest behind. So much of his people’s water had gone into keeping this damn ox alive, but the crows of these lands always took their due. He should have known the moment he saw them scatter that his luck would turn. They would come from miles around for this celebratory feast to his stupidity.

He sliced what he kept thin—no thicker than two fingers stacked—and cut the fat away. Fat went rancid first. The lean would last. Cooking would lock in the juices and ruin them by tomorrow. What he needed was smoke.

He built the fire small and patient, feeding it until it gave him a bed of coals. Then he dragged the coals aside into a shallow trench and laid punky wood and damp leaves over them to smolder. Smoke came slowly—gray, steady. It wasn’t sweet like hickory, oak, or maple. It would be bitter with pine resin and leaf ash, but he would make do.

He found a sapling not yet killed by poisoned water and cut two green branches for uprights. Another became a crossbar. He hung the strips, so they didn’t touch, then tented the frame with a scrap of ox hide, making a low hood that trapped the smoke and kept the heat gentle.

Orlan sat back on a rock and waited. He watched the sun. He hated to spend daylight like this—hated the smoke most of all, the way it turned him into a signal in the Scourge—but his stomach would thank him later. A crow dropped from the dead oak and hopped toward Hob, bold as hunger. Another followed. They didn’t go to the carcass. They watched Orlan instead—heads cocked, patient—like judges deciding whether to settle for ox or wait for the sweeter meat that still believed in prayer

Discover more from Author Scott Austin Tirrell

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Seems like a good first chapter with a promise of a good tale to follow. Have you thought of self-publishing on Patreon, with a subscription for new parts as you write them?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I haven’t looked into Patreon too much, but I will.

LikeLike

I’m hooked! More please 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You got it!

LikeLike

I love this, Scott! It reads easily and I like the way you get so many visuals in without slowing the pace. I really do want to know what happens next…!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike